How Oral Bacteria Become an Enemy!

The oral environment has various microbial communities, and understanding the oral microbiome and the ecological balances inside the mouth is essential for oral health. Oral microbes live in continuous antagonistic/mutualistic interactions, and disrupting this equilibrium leads to overgrowth of particular species that could be pathogenic.

Healthy oral cavity can be still colonized by hundreds of bacterial, viral and fungal species; still this diversity is governed by host factors. For example, the buccal/palatal mucosa has lower microbial diversity compared to the tongue, which has more papillae that host a higher number of a more diverse microflora. Dental plaque accumulates onto the teeth to form a thick bacterial biofilm, which are, together with other bacterial species in the gingival crevices and periodontal pockets, the causative of gum infections.

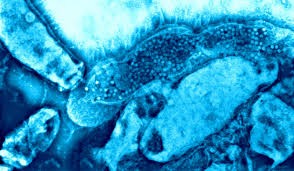

Oral bacteria can produce adhesins and other extracellular factors that facilitate the bacteria to glue onto teeth surfaces and to bind together forming bigger colonies. These factors also contain signaling molecules that facilitate synergistic communication between different bacterial species. This communication is important as bacterial cells undergo a cross-feeding mechanism through metabolic signaling, and understanding these signals is vital in analyzing the oral microbiome.

The mycobiome, or the fungal microbiome, has a huge number and comprises potential oral pathogenic residents. Candida is the most prevalent fungal species in the oral cavity, and it has cross-feeding with streptococci which synthesize carbon and lactic acid that are essential for Candida growth and persistent in the oral cavity.

The host immunity thus must differentiate between different micro-organisms, which can be either pathogenic or commensal. However, some microbial residents under certain conditions become pathogenic; and, therefore, setting this immune system can be a complex and dynamic task. Natural immune responses are tolerogenic in the oral cavity; for example, the oral mucosa presents a more immune-privileged site as pathogenic bacteria develop on there. The tolerogenic state is known as adaptive immunity which is maintained through the dendritic cells (also known as antigen-presenting cells (APCs)) that release proinflammatory cytokines, anti-inflammatory immunomodulators (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β, and Prostaglandin E2) which suppress the activity of the immune system.

Studying adhesins and other virulent factors helped in understanding how commensal species turned into pathogenic, and this in turn aided in recognizing bacteria which possess pathogenic potential. Gram-negative, anaerobic species accumulate in the gingival pockets causing periodontitis, and it is interesting to know that increased candida activity offers excellent medium for P. gingivalis invasion that result in a more severe form of periodontitis and even systemic diseases.

Another significant role of oral microbiota is their ability to induce bacterial interference (also known as colonization resistance), that is, the unique social organization of oral bacteria has antagonistic action against infection with other bacterial species.